The 'open' work

John Cage is famous for wanting his pieces and performances to facilitate a particular mode of listening in which there is no qualitative difference between the sounds issued forth by the instruments and performers–what we conventionally call the 'music'–and the unintentional everyday sounds that 'surround' the performance–what we conventionally call 'noise'. Yet, when listening to his music written for conventional musical instruments, as much of Cage's music is, some qualitative and categorical differences always remain. These differences are particularly pronounced if you attend a live performance and can identify the musicians and sound sources with your eyes and ears. For example, when playing One^6 for solo violin, it is obvious what constitutes the 'music' (the sounds from the violin) and what constitutes the everyday sounds (everything else). Windsor (1995) writes that "the sources of such 'musical' sounds [conventional vocal and instrumental music] are easily identifiable as originating within a specialized cultural domain". Therefore, "such music does not sound like the everyday environment" (136). If Cage's top priority were to completely erode the categorical difference between 'musical' and everyday sounds (and if this was a higher priority than, for example, creating beautiful pieces of music), he would have used different compositional methods and different sites for his performances. He perhaps would have taken approaches similar to sound artists such as John Wynne or Max Neuhaus, in whose work it is often literally difficult to distinguish sounds that 'belong' to the 'piece' (which usually is an installation rather than a concert piece) from everyday sounds. In their installations, the cognitive act of doubting whether a sound comes from the 'piece' or the surroundings, or maybe even from inside the spectator, is a big part of the experience that Cage never seems to attempt in his pieces.

In this text, I will describe Cage's music as moving towards eroding the difference between art and non-art, or, more precisely, eroding the difference between the artwork and its surroundings. Even though there might never be a true non-distinction, Cage's music is 'open' to its surroundings in a way that is not achieved, or even attempted, in much other instrumental art music.

In what follows, I will attempt to elucidate this openness as a feature of particular musical attunements and of particular modes of listening. This makes my purpose here different from the writers who have discussed the erosion between art objects and their surrounding worlds on a more 'general' and non-phenomenological level. For Jacques Rancière, to give an example, all great works of art are by definition 'open' because "genuine art is what indistinguishes art and nonart” (Chow et. al. 2011, 44). For Rancière, it makes no difference if a piece is a land-art object on the shore that the waves will wash away in 15 minutes or an 18th-century landscape painting with a frame in a museum. If they are 'genuine', they will both indistinguish art and non-art. Foucault, to name another example, described any book as "not simply the object that one holds in one's hands… and [how] it cannot remain within the little parallelepiped that contains it: its unity is variable and relative" (2002, 25) For Foucault, books are always expansive beyond their edges, and this holds true independent of the particular book's content; it does not matter if a document contains a poem that is designed to make the reader aware of the font in which the words are set and the paper upon which it is typed, or if it contains the kind of writing that calls for the reader's complete absorption in a narrative flow that completely makes her forget about the pages she is turning. We can also in this context remember the aesthetics of Heidegger–who we will meet again later in this text–, for whom artworks are peculiar moments in which a kind of strife between art's thingness and the surrounding world takes place and where artworks have a strong world-creating purpose. For all of these philosophers, art always involves some ways in which the art objects are 'open' to their surroundings.

We can agree with these philosophers that ontologically, the open and 'relational' nature of art is always true. All experiences, subjects, and objects are mutually interdependent and in the final analysis, it does not make sense to talk about separate objects or discrete experiences. According to the Buddhist standpoints that inform my writing, everything is empty and relational. This kind of reasoning is itself important, and I will draw upon it towards the end of this text when discussing aesthetic 'qualities'. In that discussion, we will see that aesthetic qualities are impossible to pin down and ascribe to any sound. Just like when trying to define what constitutes a 'book', the actual 'quality' is constantly slipping away. From an ontological view, it is obviously the case that any 'piece of music' by definition is 'open' to what surrounds it. Trying to pinpoint its edges as something separate will be, as the Madhyamika thinkers have shown us, illogical.

Contrary to this ontological approach to the idea of 'the open work', I am interested in how 'erosions' between art and the everyday appear as features of the experiences of listening to certain pieces of music. Ontologically speaking, all works may be open. Phenomenologically speaking, they may be not. Foucault is correct in that all art experiences are contingent upon, open to, and inclusive of phenomena besides the work. Yet, one kind of art feels more like a series of 'isolated events' whereas another kind of art feels more 'open' to the external environment. Besides trying to capture this openness phenomenologically, I am also interested in it from the viewpoint of poetics. From our experience of listening, we know that certain modes of listening are more 'open' to the outside than others, but what are the features of the works that make them so? How do musicians and composers make this happen? I am interested in unpacking the affordance structures that can bring about such erosion.

When I talk about a piece's 'openness', I am not talking about some kind of distinction between realism and fiction with regards to the content of an artwork, but a difference in the arts' 'material' appearance. In terms of music, however, an aesthetic quality of 'realism' that uses sounds that might naturally occur in our everyday environments is not completely irrelevant to the openness I will discuss in this text. As we will see below, using such 'found sounds' that might naturally occur in our environment is a strategy that can lead to the music being less of "a specialized cultural domain" (Windsor 1995, 136) and therefore opens up to its surroundings. Yet, it is important to emphasize that this aesthetic quality of realism is by no means necessary to achieve openness.

Furthermore, what 'openness' here refers to is not the same as intended by Bourdieu, Eco, and Nattiez in their discussions about openness in art. For these authors, openness was about how art allows for a plurality of signifieds by being "intrinsically and deliberate polysemic" (Bourdieu 1984, 3). For these authors, openness refers to freedom of interpretation and an 'open' (in other words, unfixed) meaning. Yet, just as with the idea of found sounds mentioned above, this aspect too is not irrelevant to the openness that is the focus of the present text either. A primary technique that Cage used to achieve the openness that I am interested in is the stripping away of symbolism, narrativity, and musical emotions from sounds to make the audience hear sounds in and of themselves. As we will explore in more detail below, when sounds are heard as mere sounds, they become transparent and open to their surroundings. These mere sounds, however, are not just barren, clinically pure, phenomena but become fertile sites for all kinds of leaps of the imagination of, what Kant called, the mind's free play. In other words, mere sounds are 'intrinsically polysemic'. So in this sense, the polysemic openness is related to the 'material' openness that I will focus on in this text (on this topic, see further discussion in LaBelle 2006, 9-10).

The 'virtual' world

As we have seen above, openness in music can refer to many different qualities. In order to pinpoint the kind of openness that Cage was interested in (the focus of this text), it is useful to understand what musical practices Cage was reacting against. Simply put, Cage was against the idea that music must be what DeNora (2000) called a "virtual reality" (157). A romantic symphony is a virtual reality because it establishes itself as a world different from the world where the music is performed. The complete acoustic mass of phenomena is divided into one layer of what Ihde (1990) called a "smooth tonality" (that is affirmed) and another layer of noise (that is rejected). Erik Wallrup (2012) gives a sensitive description of the relationship between the sounds 'around' the music and the 'virtual world' of that kind of music:

"In the phenomena of musical attunement, the temporality of the music is the temporality of the listener, and that accounts for the spatiality, mobility, and materiality too. When something around the listener intrudes, when he becomes aware of someone making a noise in the audience, when the light in the concert hall is changed, or a person starts to walk around, then the spell of the attunement runs the risk of being broken. The listener is not in the everyday world, but in the world of the musical work, a world without time and space, but with temporality and spatiality, with mobility and materiality. The listener does not identify himself with the work, because the identification can only be made when there is a distance between subject and object from the start; he does not let himself sink into the music in an emphathetic act, since the subect in that case has to move itself in a specific direction. Both alternatives call for a reflection or at least an intentional act, which is incompatible with the attunement." (Wallrup 2012, 233)

If Ihde's separation of a "smooth tonality" and noise seems like a cognitive act of 'classifying' sounds as either 'music' or 'non-music', Wallrup's perspective emphasizes how this dualism expresses itself from an attunemental perspective. When being thrown out of the virtual reality of music, it is not as if 'dirt' (e.g. noise) suddenly has been thrown on the 'smooth screen' of 'tonality', but rather it is the case that the outside noises do not make sense with the materiality, mobility, temporality, and spatiality of the musical attunement that we are nondually attuned to when listening 'to' music–the musical attunement that we simply are. Music listening is not so much, as DeNora wrote, to "abandon, albeit temporarily, the realm of material and temporal being" (2000, 157) but rather to be attuned to a musical world where a different material and temporal being takes hold. Cage's music was from this perspctive not about creating a screen onto which both dirt and purity could co-exist, or a way of categorizing sounds in which all sound types were considered 'music', but about creating a fundamental attunement–a world–where the materiality, temporality, mobility, and spatiality of the everyday world were allowed to be present in the musical attunement.

If we define Cage's openness from this attunemental perspective, where the goal is to create a porous and transparent attunement that does not exclude the materiality, mobility, temporality, and spatiality of whatever indeterminate ambient phenomena that might occur in the same space as a piece of music is performed, then this definition is still not enough to precisely capture the kind of openness that Cage's music achieves. This is because the music of composers associated with the acoustic ecology movement, who created outdoor pieces in which the sounds of nature literally became part of the music, also fits this definition. Cage's approach was different from these composers in that his music was not merely about having ambient sound becoming music or music becoming ambient sounds. Although this might have been his intention with 4'33", his later pieces, which I in this text take to be paradigmatic of Cage's approach, achieve a different kind of relationship between the music and ambient sounds. In his later music, Cage managed to make everyday phenomena welcomed into the experience without transforming them from their status as primordial indeterminacy–without being turned into musical objects. In other words, the musical attunement was open to co-existence with ambient sounds, but did not colonize ambient sounds–did not bring these into the musical syntax in the way some outdoor pieces by acoustic ecology composers attempt to.

The music as a process

When listening to Cage's late Number Pieces, the Cage interpreter Rob Haskins describes the feeling of how the music more and more is "taking equal precedence" with the other events around him. It is "gently enveloping" him until he sees and hears "minute details of everyday life with a fresh, uncluttered clarity". To this, he adds a statement expressive of wonder: "Perhaps this experience transcends any emotional reaction I could have" (n.d.). In his sensitive writings, Haskins describes how Cage's late music manages to integrate with the sounds of the everyday to some extent ("more and more", but never fully becoming non-discernible from them) and how this leads to a meaningful aesthetic experience ("transcends any emotional reaction I could have"). This passage by Haskins is in harmony with my own approach to Cage's music: the purpose is not for the music to 'become' the environment but about bringing about a changed relationship to this environment–seeing it with a "fresh, uncluttered clarity". This changed relationship is not brought about by way of the music being submerged in the environment completely but rather by gently intimating it through sound.

It is, therefore, a mistake to say that all there is to Cage's music is an intention to create situations where sounds 'just happen', where all boundaries between 'art' and the everyday are eroded, or where the music sounds like the everyday environment (since a violin obviously does not). This point is also emphasized by LaBelle when writing that Cage's music "initiates a conversation in which the musical and found sounds merge, making music a cultural paradigm beholden to sound and its situatedness" (2006, 21). For there to be a conversation, the musical and found sounds cannot merge completely. Cage knew that musical sounds never could be perceived as the 'just sounds' of the ambient environment, and that was never the point. The point was rather to through music, open up for poetic encounters with ambient sounds; the kind of profoundly meaningful poetic encounters that Haskins describes as transcending any "emotional reaction".

Contrary to a musical piece being something autonomous that can be 'moved around', Cage's music was to be perceived as something impossible to distinguish from 'the time and place' in which it was performed. Cage, therefore, referred to his own music as a process rather than as an object. Unlike an object, a process is not something that one can simply 'drop into' time and place but something that necessarily becomes part of that time and place, but, in Cage's case, still is recognizable as 'music'. In Cage's processes, there is still a difference between the musical sounds and the everyday environment, but both are present and part of the same process.

Because of Cage's preference for art that does not isolate itself from its environs, there is a real connection between Cage's music and the aesthetic concerns that motivated the emergence of site-specific art in the 1970s. Like Cage's music, this art seeks to replace the "pure idealist space" of modernism with "the materiality of the natural landscape or the impure and ordinary space of the everyday" (Kwon 2002, 11). Most of Cage's late pieces are not site-specific per se but have a porousness and adaptability that makes it possible to perform them in different kinds of spaces and always manage to bring the space and its sounds into the same process as the music. It is similar to some of the sculptures of one of the representatives for site-specific art, Lee Ufan. The basic structure and elements of the particular pieces are pre-determined, but the sculpture's use of open spaces and by allowing the exact placement and configuration of the pieces' elements to be malleable enough for each iteration allows the pieces to feel site-specific. Since there is a clear connection between Cage's work and Lee's, and because Lee's writings on this process are so detailed and insightful, Lee's writings will be drawn upon later in this text to help elucidate aspects of Cage's music.

The difference between processes and objects was introduced by Cage in a discussion about silences. Regular Western music–objects–had 'musical silences' but Cage's music–processes–had 'ordinary silences'. Cage included among objects even some of his own early pieces. The silences in them were similar to the silences in Western classical music–the kind of silence that makes the music perceived as an object rather than as a process. Even though he approved of the noticeable inclusion of silences in his early pieces, the silences were too dramatic and pregnant with energy. Such silences close the piece down and prevent them from opening to the everyday–prevent them from having the quality of ordinariness.

To some extent, I agree with Cage that his early silences feel a bit more dramatic, but I personally find some of them to be open as well. I am thinking here about the first long silence in the first movement from Two Pieces for Piano from 1946. I remember very clearly the first time I heard this silence and how the emptiness of ordinariness was revealed to me therein. Even the gorgeous silences in Four Walls from 1944 are worth mentioning. These silences are often preceded by short attacks–it is not the case that they come about from sounds fading away. We might think that this means that the silences will be filled with anticipation, but for me, this is not the case. But it is certainly true too that they do not have that serene ordinariness that the silences in for example the Number Pieces have.

Cage famously said that "there is no such thing as silence" because there is always the background noise of the everyday present. Francisco Lopez (1996) argued against this Cagean axiom by saying that silence does actually "exist; in music". What it means for silence to exist in music is that the quality of the silence is such that the 'everyday noises' are not allowed to presence. They are simply 'ignored' by the categorizing mind. It seems that Lopez had missed that Cage already had provided an answer to this critique in an interview with Jonathan Cott, in which Cott makes a similar remark as Lopez's by pointing out that musical silence is opposed to ordinary silence "because it is created within the framework of the composition by that first sound" (1963). Because musical silence is different from ordinary silence, we can, according to Cott and Lopez, say that silences exist in musical listening, and hence, there is such a thing as silence. Cage's reply was: "Certainly if we are speaking about objects, you see". This is where Cage introduces that distinction between objects and processes. Contrary to the pieces of the Classical standard repertoire (objects), Cage creates processes where the "framework of the composition" that Cott mentions does not appear. Rather than closed structures, they are perpetual states of becoming. The 'framework' of the composition–or the kinds of 'strong' musical worlds that Wallrup has in mind–does not appear. Because these processes are continuous with everyday life, Cage's music has 'ordinary' silences instead of 'musical silences'. Therefore, in Cage's pieces, musical silences (in the way that Cott and Lopez use this term) do not exist. Cage agrees with Cott that 'musical silences' exist in other music, but not in his own. So when Lopez argues that there is silence in music, he would be correct given most modes of listening, but not the one that Cage was trying to attune us to.

Different kinds of silences

There is a story that problematizes the silences in Cage's music in an interesting way. The story, told by Brooks (2010), takes place during a concert where Cage's violin solo Freeman Etudes was being performed by Paul Zukofsky. During the performance, a creaking door disturbed the audience, but no one dared to close it because they were all familiar with the ideas of Cage (who was present in the audience), and how Cage did not believe in any distinction between environmental and musical sounds. They were probably all too familiar with the story, often retold by Cage, of Christian Wolff playing the piano with the windows open to outside traffic, the sound of which often washed over the music and made the sounds of the piano inaudible. Despite this, Wolff did not consider this to be an obstruction to the enjoyment of his music:

"One day when the windows were open, Christian Wolff played one of his pieces at the piano. Sounds of traffic, boat horns, were heard not only during the silences in the music, but, being louder, were more easily heard than the piano sounds themselves. Afterward, someone asked Christian Wolff to play the piece again with the windows closed. Christian Wolff said he'd be glad to, but that it wasn't really necessary, since the sounds of the environment were in no sense an interruption of those of the music." (Cage 1967, 133)

At the Zukofsky concert, Cage himself eventually got up and solved the problem by adjusting the door to stop the noise. Inevitably, during a Q&A period, Cage was questioned about this and Cage defended himself by describing the Freeman Etudes in this way:

"What you have is an extremely complex situation, like poetry condensed in time. You have only a brief moment to hear a very complex situation which, it is true, is open to noises; but I don't want to hear them because I don't know these pieces very well yet and I don't have very many chances to hear them” (Brooks 2010, 61)

This statement from Cage seems to contradict some of the arguments I have laid out this far. It seems as if Cage meant that he had not yet familiarized himself enough with the piece to 'let it be open,' as if prior familiarity with pieces is an important aspect. If this were true, then the whole attempt of trying to locate the capacity for music to open in the affordance structures of the music would be thwarted: what determines if a piece can open or not is instead located in the 'subject'–whether they are familiar enough with the piece to let it be open. For the argument that this openness is causedby something in the music to work, the music must open spontaneously, not be dependent on previous listenings or degrees of familiarization. Alternatively, we could say that the Freeman Etudes are not good examples of the kind of open pieces I describe in this essay. Haskins, for example, almost exclusively discusses this quality in Cage's Number Pieces, which are much slower, less busy, and lack the kind of energetic gestures that characterize the Freeman Etudes.

It is therefore important to recognize that different pieces, even when written by the same composer, call for different enactments of silences; not all of Cage's music calls for 'ordinary silences'. Something like this is also expressed by Jürg Frey in an interview. Being a 'Wandelweiser' composer, he gets asked the question—that I assume he gets asked a lot—if it's OK that there is ambient noise in his music’s silences. He answers that it depends on the piece:

"That’s an interesting question. I have silence in a lot of my pieces, and the answer to the question isn’t the same for every piece. In my String Quartet No. 2, for example, I think it sounds best when it’s silent; when the audience is concentrated. They can be sitting or lying down on the floor or whatever, but there shouldn’t be additional distractions. No sandwiches to eat during the concert, and no walking in and out. It’s 30 minutes, and you should just try to concentrate. Of course your mind wanders—that happens to me too. It’s not like I listen to the piece and for 30 minutes I’m completely concentrated on every note. That’s totally normal. That might be less true for other pieces of mine. If they’re longer, or if they have more silence, then it’s worth considering whether the performance situation should be different. But for the String Quartet No. 2, concentration matters." (Brown 2017)

The question then becomes how Cage creates 'ordinary silences' in some of his pieces. The answer seems difficult to find in the silences themselves since they are perceived differently due to the surrounding sounds and have little 'say' over their reception themselves. To say that Cage achieved 'ordinary silences' through his particular use of silence is like saying that a patch of color is red because it is red. Lengthy silences seem to be a recurring motif in 'ordinary silences'. When describing a particularly compelling listening experience quoted in full below, Cage notes that the silences are "extremely long". But long silences are not important because of the duration in and of itself, but rather because of what a long musical silence does to the musical flow and how the constant 're-starting' of the music that long silences suggest creates a perpetual focus on the music's beginningness–a quality that we below will call the quality of aperture. Besides saying that the silences are long, the search for ordinary silences seems to only be found in the sounds that surround silences.

Just sounds

Turning therefore from silences to sound, it has already been said that Cage seeks to create sounds that neither merge with the ambient sounds nor create a virtual world. The goal is to create a piece of art that is 'open' and that transforms the audience's encounter with what surrounds the art, but without the art becoming submerged in it. The art, the sounds, can be said to be mediators, a term introduced by Lee Ufan, who in his sculptures parallels Cage's attempt to create something that is neither the environment ("reality") nor something completely separate ("an idea"):

"A work of art can neither become an idea as such nor reality as such. It exists in the interval between idea and reality, an ambivalent thing that is penetrated by and influences both. My work is not the creation of modernist totalities or closed objects. It is important to create a stimulating relationship between what I paint and what I do not paint, what I make and what I do not make, the active and the passive. […] That is, by limiting the act of making and combining it with things that are not made, I incorporate externality and reveal a non-identified world. [...] Just as humans are physical beings, points of contact between internal and external worlds, works of art must be living intermediaries that mediate between and exalt the self and the other." (2018, 51)

Lee was deeply influenced by Heidegger, and in his thinking about mediators, one can sense the impact of Heidegger's idea about how artworks are sites for a kind of strife between the non-objective world and the art's thingness (also called "earth"). In an evocate passage, Heidegger speaks of how both the sculptor and the mason use stone, but what makes the sculptor an artist is that "he does not use it up". The same is true for the painter: "the painter also uses pigment, but in such a way that colour is not used up but rather only now comes to shine forth" (Heidegger 1971b, 46). Lee writes in a passage with clear echoes of this part of Heidegger's argument that "[t]he task of the artist is to transform just what is into just what is" (2018, 251). Transforming the material of art into just what is–by allowing the art's thingness to be present in this heightened way–is precisely how openness is brought about because it brings into the experience both the non-objective world as well as the thingness: "The setting up of a world and the setting forth of earth are two essential features in the work being of the work. They belong together, however, in the unity of work being" (Heidegger 1971b, 46).

What makes Lee's approach unique, however, is that while the world for Heidegger is what we perhaps with Buddhist terminology would call saṃsāric–it is the world that makes human life intelligible and meaningful to persons (Skrt. pudgala)–the exteriority that Lee's art opens up to is the dharmakāya (Lee 2011, 112)–it is emptiness. The "non-identified world" is not so much the background practices that make up a culture (as in Heidegger's case) but the field of indeterminacy from which phenomena appear as emptiness.

For the art to function as a mediator, there has to be a balance between openness and constraint: the work must fuse with the world "while remaining separated from other things" (2018, 251). Lee writes that

"[t]he act of simply pointing to a rock on a river bank might be called a work of art. In such a case, however, the limitations placed on the stone might be too slight, and there is a danger of the work being completely submerged in nature." (Lee 2018, 251)

In other words, if the work is too open, it will no longer perform its function to open. "On the other hand," Lee continues, "if I work on the stone and carve it into a human figure, the constraints placed on the work are too strong and there is a danger that it will be totally closed off from nature" (2018, 251). The art would then start to function like autonomous objects that do not invite to anything but the act of ignoring its surroundings.

Lee's description can be transposed to the analysis of Cage's music: the sounds of musical instruments act as 'mediators' between the music and the indeterminate emptiness surrounding the music. These mediators make present the openness of the "non-identified world" but without making it identifiable as something. In order for this to occur, the music can not strive to completely sound like the ambient environment. Rather, it has to be a "contradictory structure" that is "simultaneously unified and divided" (Lee 2018, 251). As LaBelle (2006) was quoted above as saying: the musical and found sounds must both be in a conversation and also merge–they must be both divided and unified. A musical example that is too closed to open could be the Romantic symphony that creates its own virtual reality. In these kinds of pieces, the ambient sounds are ignored because they do not belong to the world of the music at all. An example of music that is too open for emptiness to presence is Cage's own 4′33″. This is because this piece simply does not have any mediators: it is completely silent, and the ambient sounds presencing in this silence do usually not have the mediality it takes to function as mediators. Paradoxically, the ambient sounds instead become the foreground of the music and turn into objects of attention (which, as mentioned above, was Cage's intention with this piece). In 4′33″, we, therefore, do not hear silence as emptiness.

There is, however, a crucial difference between Lee's way of formulating himself and LaBelle's. In LaBelle's case, the sounds of Cage's music are mediators between musical sounds and found sounds. In adapting Lee's poetics to the music of Cage, the sounds of Cage's music are mediators between musical sounds and emptiness. The difference is that emptiness is a "non-identified world" and indeterminate, while the found sounds are simply the sounds that occur in the environment–sounds that can become the object of focus. The way I read Cage, and why Lee is a good explicator of Cage's music, is that the purpose of the musical sounds is not to make us hear the ambient sounds but instead to make us have encounters with indeterminacy. For this to happen, the ambient sounds are neither ignored nor made into foregrounded objects of perception. When Cage describes an ideal musical experience as being like "not listening to music" and as just being about experiencing how "sounds simply happen" (1981, 119), I do not interpret Cage as actively hearing ambient sounds as objects–as if listening to the sensuous sounds of a field recording–but that he was letting phenomenality arise as emptiness–not listening to anything but also not ignoring anything. It is the indeterminacy of the situation that is relished, not so much the 'found sounds' that the ambient field provides.

The way in which Cage's makes his sounds function like mediators is by giving them a medial quality. When music 'hides' its medium by creating an obscuring 'veil' of sound, an artificial dualism between the music and the rest of the phenomenal field is created. An example of this kind of music mentioned above is Romantic orchestral music. This kind of music creates veils of sounds that hide sound's transparency by way of conjuring up 'musical illusions'. These kinds of veils cause a phenomenological separation, in the mode of listening to this music, not only between musical sounds and the surrounding ambient sounds but also between the "smooth tonality" (Ihde 1990) and the noisier aspects of the sounds that make up music–the aspects that reveal more about what kinds of sounds that the sounds are. As Scruton (2009) has suggested, the nature of sounds is already in a sense to be insubstantial and illusory–they are like rainbows or echoes–, but Romantic music hides this basic kind of illusoriness by transforming these sounds into something that becomes distinguished–separated–from the complete phenomenal field. It is like carving out a realistic human sculpture out of natural rock. The shape of the rock is given a life of its own, an expressivity and source of meaning. The sculpture both 'hides' what it is made out of and in so doing, stands out from the phenomenal field as something separate. One strategy to not cause this phenomenological separation is therefore to draw the listeners' attention to the sounds themselves–to just sounds, to just what is. When sounds draw attention to themselves in this way, they have the quality of being medial.

In their 2007 book Ecology without Nature, Morton describes how mediality necessarily performs a kind of 'ambient poetics': it conjures up or brings to life the atmosphere (the ambiance) surrounding the artwork. Moments of mediality always have the dual properties of both being 'self-reflexive' (sound is just sound, not trying to be something else) and therefore also 'open' to the surroundings. The medial quality reveals that music is made out of the same 'stuff' (i.e. sounds) as the everyday and does therefore not create a disembodied 'virtual world' outside of it. In making the medium itself the main focus of the art by drawing our attention to the details of sound, the transparency of sound is revealed. Mediality therefore necessarily means that the sounds function as 'mediators' in Lee's sense that was introduced above: sounds that are medial become mediators between the created and the un-created.

In Ecology without Nature, Morton uses the violin as an example to elucidate the quality of mediality. They write that a medial musical passage for the violin is a passage that makes us "aware of the "violin-ness" of the sound—its timbre" (2007, 37). Morton does not say more than this here, but in the subsequent books The Ecological Thought (2010) and Hyperobjects (2013), they flesh out this idea of writing music for instruments that has as its sole content the sound of the instrument. There, they emphasize that musical sounds that have this quality lack the quality of merely sounding like "materials-for (human production)" (2013, 172). Rather than sounding like they express human emotionality or the inner lives of composers, the sounds are only about themselves:

"Gradually the inside of the piano freed itself from embodying the inner life of the human being, and started to resonate with its own wooden hollowness” (2010, 165).

One composer that Morton singles out as instrumental in this is Cage. Morton writes that "Cage's prepared piano makes us aware of the materiality of the piano, the fact that it is made of taut vibrating strings inside a hard wooden box" (2007, 38). Cage, with his pieces for the prepared piano, was the first composer, according to Morton, to free himself from his ego and start to actually listen to the instrument. Cage did not, according to Morton, write sounds to voice his inner being, but rather gave sounds their own "anarchic autonomy" (2013, 165). Here, Morton is conflating different parts of Cage's career: the Sonatas and Interludes for prepared piano were written to express the eight "permanent" emotions as explained in Indian rasa theory–the humorous, the wondrous, the erotic, the heroic, anger, fear, disgust and sorrow (Kostelantz 2003, 67), while the idea of presenting sounds as single points in a kind of anarchy is more associated with his later works, such as the Number Pieces. The idea that Morton is expressing is nonetheless that by paying attention to the sounds of instruments in a way where their 'materiality' and 'autonomy' are the sole content, we can hear the sounds in their uniqueness and as-is-ness; they are not just face-less sound sources that are supposed to create an acousmatic veil or express human emotions.

The way I understand Morton's theory is that sounds can sound like just sounds when we don't impose human emotions, intentions, or stories onto them. We should neither try to 'manipulate' the sounds nor treat them like "materials-for". On the one hand, we might say that certain sounds, due to their unique timbres, have a way of drawing attention to themselves almost 'naturally' or 'automatically'. In the case of Cage's prepared piano, for example, the inherent noisefulness, complex timbres, and heterogeneity of the sounds seem to have a way of drawing our attention to the sounds themselves. On the other hand, it is primarily a matter of compositional articulation that brings mediality about. Any sound can sound like a just sound, and it is possible to write music for Cage's prepared piano that fails to draw attention to the sounds themselves. The strategies that Cage used to achieve mediality–the nondual sense that just sounds are simultaneously the medium and the message and that there is nothing other than just sound–are essentially acts of negating a lot of the strategies that conventional music employs. Mediality comes about when we use qualities such as no-continuity, non-symbolism, non-narrativity, and none of these qualities actually reside in sounds themselves. It is the musical context–all the other sounds preceding a particular sound–that determines whether a sound is perceived as symbolic or non-symbolic. The key here is that, as Morton writes, when music no longer sounds like it represents human emotions, it will start sounding like a collection of just sounds. The quality of mediality can, therefore, not be located in the sounds themselves. We can, therefore, not say that using just sounds constitutes a strategy for achieving Cage's mode of listening, but rather that this concept expresses what it sounds like when other qualities (or negation of qualities) have been employed.

Aperture and beginningness

As said above, sounds that have a medial quality are both 'self-reflexive' and 'open' to the surroundings. It is not just about drawing attention to sounds for the sake of bringing about a more 'detailed listening' to the sounds produced by instruments. Rather, it is about bringing about a situation in which the sounds become 'open' to their surrounding. Morton writes that the medial "undermines the normal distinction we make between medium as atmosphere or environment—as a background or 'field'—and medium as material thing something in the foreground" as it "seeks to undermine the normal distinction between background and foreground" (2007, 38). Medial sounds are mediators between sounds and their surroundings. As contradictory structures (Lee 2018, 251), they have aspects of both background and foreground.

While openness is a feature of all mediality, Morton singles out an even more precise aesthetic quality that captures what happens at the edge between the art piece and its surroundings. This quality is called aperture. If medial art draws attention to itself, the term aperture captures even more explicitly how this also involves drawing attention to its edges, its aperture, and its opening to the surrounding world. Speaking of art's aperture captures the feeling of how the 'beginning' and edges of art's material–its thingness–are clearly felt and experienced. A frame around a typical 19th-century landscape painting does not give the art the quality of aperture; the frame's function is rather to seal off the painted landscape from the wall and create a window into a different world. Morton analyzes the quality of aperture as a crucial aspect of minimalist painting and sculptural practices where there often is no frame:

"where does the work of art begin if there's no frame around it—and if the work is only a frame with a blank, we are left with the same question" (2010b, 38)

When the aperture of sounds is clearly manifested, it becomes impossible to experience the 'piece' as a virtual world on its own. This is because worlds are all-encompassing wholes. A world is something that one simply 'exists in', copes with, and does not have to think about. Worlds are not objects but the referential wholes from which individual objects can stand out. With a sense of aperture, the heightened focus on the edges and beginnings makes it difficult for the music to establish a virtual world separate from the everyday.

Takemitsu (2004) tells a story that illustrates how the quality of aperture can lead to the opening up of music to its surrounding environment. He is having dinner with a shakuhachi musician who, during their dinner, performs a piece. The shakuhachi is an instrument that easily invites a great focus on the materiality of the instrument–just as with the prepared piano, we can see how the aspects of noise, timbral complexity, and heterogenous scales help bring this about. Its honkyoku repertoire makes use of this, and the way one listens to it is with very detailed listening to the sounds and their becoming. The frequent silences that punctuate the music allow for the contact between the sound and the surrounding environment to become heightened and brought into focus. This contact becomes an important part of the 'content' of the music. This quality of aperture expands the world of the music to not only the sounds produced by the flute but the entire phenomenal field. During the performance, Takemitsu becomes at times even more aware of the sizzling sukiyaki and the ambient sounds around them than the flute. When commenting on this, the musician takes this to mean that his performance was good–"then it is proof I played well" (201)–rather than taking it as a criticism of a boring performance that made Takemitsu's attention wander. A similar story is also echoed by Cage, but he ascribes it to a different source:

"I remember, when I first got involved with studying Zen Buddhism, loving those stories that came from a shakuhachi player who was also interested in cooking. The sound of the music continued in the cooking!" (Cage & Oliver 2006)

The fact that the performance not only leads to a concentrated focus on the sound of the shakuhachi but also makes the listener aware of the surroundings illustrates how the qualities of materiality, mediality, and aperture function to erode the distinction between music and its environment.

This would all be true even if the sound of cooking wasn't there. It would be a mistake to read the anecdotes above as arguing that the distinction between music and the everyday is eroded only because the sound of the shakuhachi continues in the food. Yet, because the cooking is there, and because the sizzling sukiyaki has some real spectral similarities with the shakuhachi sound, it allows, quite concretely, for the shakuhachi to continue in the cooking and for the cooking to be part of the music. This is always a real possibility with silences. Unlike the acoustic ecology composers, the composer might not have intended this to happen. Since the music creates a world in which ambient sounds are allowed to exist, however, there always consists a possibility for an unpredictable, free association to arise between some ambient sounds and the music, for some sounds of the ambient field to also, together with the sounds of music, become mediators between sound and emptiness.

The quality of aperture draws attention to the 'beginning-ness' of sound. It draws attention to the transparency and relationality of sound. The sounds do not create an exclusive 'word' of their own. In his elucidation of the phenomenology of Stimming, Wallrup finds this quality of the 'endless beginning' or the 'beginning that never starts' in the music of Giacinto Scelsi:

"Even more radically, pieces like Giacinto Scelsi's Quattro Pezzi per Orchestra (ciascuno su una nota sola) never begin. They are pieces of becoming, not of being. They open up spaces that never reach the status of world-hood; they never leave the phase of tuning-in since they never reach into anything, always standing on the threshold of something that is never made present." (2012, 314)

In the context of Wallrup's dissertation, this quality in Scelsi's piece comes across as something lacking. It is a kind of music that fails in 'world-building' and immersive capabilities. But this way of seeing it is to miss the point that the focus on beginnings actually opens up vaster spaces beyond the world of 'pieces of music'. By focusing on 'becoming' rather than 'being', music can draw attention to the empty ground from which all phenomenality arises and the world of the music and the world of the surroundings become the same. Here is the distinction between Lee's approach to 'externality' and Heidegger's approach clearly illustrated. Wallrup's approach is fundamentally Heideggerian, so for him, the world that is created has to be in some particularly meaningful way. Saying that some of Scelsi's pieces never reach "the status of world-hood" makes sense from this perspective. For Lee–and therefore for Cage on my view–, the externality that the music opens up to is emptiness, and becoming might actually intimate emptiness better than being. Relishing the nonduality between the sizzling food and the shakuhachi means relishing the emptiness that shines forth even as it takes on different sounding forms.

An aesthetics of ordinariness

Noël Carroll described Cage's music as expressing a "new aesthetic category" of ordinariness (1998, 128). This modal term effectively captures the feeling of how the music by Cage seems to exist in 'this world' rather than some fictional or virtual reality. Instead of being transported away from this ordinariness by music, Cage wanted to be "transported … to [his] daily life, when [he is] not listening to music, when sounds simply happen" (1981, 1119). Daily life contains an infinite amounts of moods and feeling states, but the qualifier "when sounds simply happen" suggests a kind of detachment or non-involved attitude to ordinary life. It is not about being caught up in the sounds or hearing them passionately but about hearing them with some kind of equanimity–hearing them as simply happening. To speak of ordinariness in Cage's music is therefore to point to an 'affective' quality with which Cage's music is open.

As Haskins in the quote above makes clear, the mood of ordinariness that Cage's music attunes him to is different from the kind of ordinariness that Kenneth Goldsmith (2004) expresses with his aesthetics of boredom—although such a view has been a predominant one in the reception of Cage's work (see Jaeger 2013, 82). Cage's ordinariness does not lead to boredom but rather a 'clear seeing' of the everyday without any gross emotional reactions. As an affective mood, I take ordinariness to be not too dissimilar to what in the Chinese aesthetic tradition is known as blandness (淡): the unimposing flavor that is said to taste like water. Just like blandness, ordinariness has an extremely subtle taste. It is almost not music and 'feels' more like an attunement to everyday life. It is partly because sounds do not come with any charged affects that they can arise in this way as 'just sounds'–as just what is. In this mood of ordinariness, we relish the tastefulness of sounds stripped of their conventional 'musical functions' and flavors.

Descriptions of Cage's daily life had often a distinctly meditative quality. Cage never described himself as being a meditator–in fact, he often comes close to deriding meditation by his preference for referring to it only by its 'unusual' seating position of 'sitting cross-legged'–, but he consciously described his everyday life as being full of mindful activities, such as watering the hundreds of plants he had in his apartment (1990). Cage's derision of formal meditation and praise of practical activities has clear parallels with Chán iconoclasticism, in which a simple wood chopper might be more awakened than a meditating monk, and where 'eating when hungry, sleeping when tired' is more of an awakened activity than meditating in the meditation hall. Starting during the Tang dynasty, daily activities such as wearing clothes, eating, and sleeping started to be described as the function of Buddha nature and seen as integral activities in the practice of Chán. In Chán texts, the acts of drinking tea, chopping wood, carrying water, and washing bowls were 'ordinary activities' that expressed Buddha nature (Jia 2006, 82)–they were forms of functioning (作用) that manifested nature (性). While Cage did not meditate, he still emulated the 'discipline' of meditation, and he approached his composition practice with the same discipline as that of zazen:

“Rather than taking the path that is prescribed in the formal practice of Zen Buddhism itself, namely, sitting cross-legged and breathing and such things, I decided that my proper discipline was the one to which I was already committed, namely, the making of music. And that I would do it with a means that was as strict as sitting cross-legged, namely, the use of chance operations, and the shifting of my responsibility from the making of choices to that of asking questions.” (Cage in Kostelantz 2003, 42)

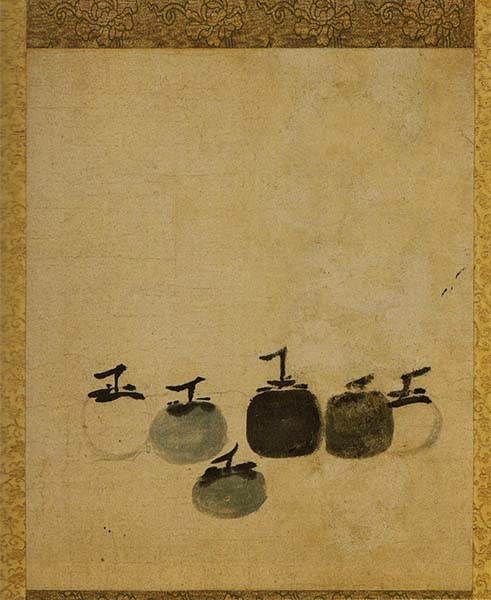

I read Cage's wish to be transported to 'daily life' against this background of Chán iconoclasticism and the valorization of ordinary activities as already awakened. Cage, when listening to music, did not want to be transported back to a feeling of depression from doing mundane tasks at an office in an oppressive capitalist system. Again, it is not some Goldsmithian boredom that Cage valorized and it is not that kind of ordinariness we are transported to when listening to Cage's music. The kind of ordinariness that Cage had in mind is rather the 'awakened everyday' that he often evoked when talking to journalists about his life. The way I see it is that Cage was successful in this task. His pieces of music are, like the Chán paintings of Muqi, 'fit for a monks' quarters'. Just as there is nothing 'Zen' in content about everyday objects such as Muqi's six persimmons, there is nothing 'Zen' in content about Cage's music, but both artists are successful in conveying a fresh perspective on reality-as-Mind and attuning their audience to an actualization of ordinary life as already awakened. They transmit some of the very same qualities that are cultivated by meditating monastics in Buddhist monasteries. Cage's ordinariness comes with that fresh equanimous perspective of hearing sounds as 'just sounds simply happening' that is cultivated in meditation. This is the 'everyday' that Cage wanted to be transported to.

As a side note–and as a way of distinguishing this ordinariness from other modal terms of similar affect–one could argue that the relishing of 'ordinariness' that was afforded by Cage's music was scaffolded by one of modernity's pervasive cultural attitudes: the affirmation of everyday life. Taylor (1989) has sketched the history of this affirmation and finds its roots in the European Reformation. McMahan (2008) writes:

"Protestant thinkers, like William Perkins, largely rejected localized, material sacrality—sacred objects, relics, places—which had the effect of leveling the spiritual landscape of the world. In the new Protestant order, no place or object was inherently more sacred than another. This began with the Reformer's assertion that each individual could have unmediated access to God and hence had no need for special places, priests, icons, or rituals." (McMahan 2008, 220)

McMahan argues that it was this valorization of the everyday that enabled Buddhist mindfulness practices to spread as easily and rapidly as they did in the West (2008, 221), and the same argument can therefore be transposed to explain the reception of Cage's music. Cage was himself raised a protestant and considered in his youth to become a minister like his grandfather. Perhaps this protestant affirmation of the everday supported the relishing of ordinariness in Cage's music for both Cage as well as his audience. It was perhaps the cultural attitude that enabled his music to be so meaningful for many members of his American and European audiences, who had no connection to things like Zen rock gardens, Buddhist practice, Muqi's six persimmons, or the poetry of Méi Yáochén.

It is, however, important to note that the 'ordinariness' that Buddhists speak of–and ultimately, I am here arguing, the ordinariness that Cage's music attunes the listener to–is different from the protestant affirmation of everyday life. The difference has to do with emptiness. Even as Mǎzǔ Dàoyī postulated that 'this mind'—commonly translated into English as 'ordinary mind'—is the Buddha (即心是仏 jíxīn shìfó) and even as he proclaimed that even while wearing clothes, eating, and talking, we are already abiding in the sāmadhi of the Dharma-nature, authenticating this for ourselves is not simply about 'valorizing' the everyday. It is rather about seeing everyday life for what it really is: phenomena as impermanent, illusory, relational, and empty. The ordinariness of Cage has an apparitional quality that makes it closer to the Chán ordinariness; things are not merely 'usual' but are seen as 'unreal' and as dreamlike.

Until now, we have identified two primary components in bringing about this mode of listening. By using silences and by letting sounds have a medial quality and draw attention to their beginnings, the music can stand in relationship to ambient sounds that allow the listener to hear the ordinary, everyday life as indeterminate emptiness. In a passage already alluded to above, Cage elaborates more on the musical qualities that bring this mode of listening about:

"Just a few weeks ago, I had a very odd experience in a Japanese restaurant in New York. In this restaurant, there was a tape recorder playing Japanese music ... We were conversing as usual while the music was playing. Little by little, during the gaps in our conversation, I realized that the silences included in this music were extremely long, and that the sounds that occurred were very different from each other. I was surprised by my discovery, because the extent of the tape was absolutely unusual, it was very long. And I had never run across that in traditional Japanese music. This piece wasn't destined uniquely for Japanese listeners, but for the entire universe, . . .and it was very, very beautiful. I was unable to recognize any tempo, any periodicity at all. All I was able to identify was the arrival of a few sounds from time to time. I was transported to natural experiences, to my daily life, when I am not listening to music, when sounds simply happen. There is nothing more delicious!" (1981, 119)

Besides the extremely long silences, the sounds were sparse, contrasting, and without tempo ("the sounds that occurred were very different from each other ... I was unable to recognize any tempo ... the arrival of a few sounds from time to time"). The length of the piece was long, which furthermore suggests that a patient and leisurely approach to musical unfolding was afforded. Haskins, in a retelling of listening to the Number Pieces that closely mirrors Cage's retelling of the music at the restaurant, draws our attention to a few more of these qualities: a slow unfolding, a leisurely approach to time, and the lack of narrativity:

"Cage's music depends on a slow unfolding and a leisurely approach to time in order to make its full impact. That slow unfolding introduces a graininess or raggedness to the beauty of the sounds. There is no contrast, no epiphany, no drama, no point. The music simply continues with almost annoying steadfastness until its end. That steadfastness, stretched out to extraordinary lengths (seventy minutes or more), allows the music to avoid the trap of merely sounding beautiful." (Haskins u.d.)

The "slow unfolding and the leisurely approach to time" give a certain function to the silences between the notes. They do not become filled with the kind of energy that often exists between notes in Western concert music. In the texts "The distance between art and awakening - Part II", "Quietness", and "Pointillism", I explore further the qualities of non-conceptuality, discontinuity, non-symbolism, blandness, zōka, quietness, and pointillism. These are are all qualities that facilitate the enactment of 'ordinary silences' and 'just sounds'.

The dialectics of sounds

In this present text, we have seen that the mediality of sounds impacts silence because it contributes to undoing the dualism between ambient and musical sounds. Because the sounds are in a certain way, the silences appear as ordinary silences rather than musical silences. But silences are just as important in giving sounds medial qualities as the sounds. If sounds were continuous, it would almost necessarily lead to the kind of dualistic veil that Lee and Cage's aesthetics try to avoid. Because of its aperture, medial sounds make the shift to silence less 'abrupt' and soften any edge that could create a dualism. Silences contribute to causing the aperture of sounds since without any silences, there could be no aperture because the quality of aperture is dependent on there being something on both sides of the opening. The qualities of mediality and aperture can thus not be completely found in either sound or silence. Above, we said that the perception of silences is primarily determined by the surrounding sounds, but this does not give the full causal story since the perception of sounds is impacted by silences.

Silences and sounds must therefore be said to be both cause and effect. Because of silences, sounds are perceived in a certain way. Because of sounds, the silences that in turn impact sounds are perceived in a certain way. Silences and sounds are causes for a mode of listening, and the way in which they are perceived is at the same time the result, the effect, of a certain mode of listening that already, through sound and silence, has attuned the listener. When studying modes of listening and trying to locate the effectivites and affordances in particular factors, it becomes clear that it is impossible to make a separation between cause and effect. Modes of listening can therefore be said to teach the non-obstruction of phenomena, as Chéng Guān said:

"It is cause and It is also effect" means that there is no cause which can be regarded as truly different from effect and vice versa... (quoted in Chang 1971, 154)

When we are musically attuned, we are musically attuned to a world. This is true even in Cage's pieces that manage toleave this world open to ambient sounds. The world is the non-conceptual "something other" that makes sounds and silences appear as intelligible–as being part of a world. But the sounds and silences themselves are what cause the world since there would be no world without them. The world does not exist independently before sounds and silences. Sounds and silences are therefore always cause and effect simultaneously. World and sound are simultaneously established and include each other. The world is comprised of all sounds and silences, and each sound and silence is heard as that world. Since all sounds and silences take in the whole world, this means not only that the world is included in every sound, but that every sound of that world is included in every other sound, since sound and world contain and cause each other. Thisis what in Chéng Guān's Huáyán school is called the shì shì wú ài (事事無礙)–the non-obstruction of phenomena. Gregory (1991) explains the shì shì wú ài–also referred to as 'conditioned origination of the dharmadhātu' (法界緣起 fǎjiè yuánqǐ)–in the following way:

"The conditioned origination of the dharmadhātu means that, since all phenomena are devoid of self-nature and arise contingent upon one another, each phenomenon is an organic part of the whole definied by the harmonious interrelation of all its parts. The character of each phenomenon is thus determined by the whole of which it is an integral part, just as the character of the whole is determined by each of the phenomena of which it is comprised. Since the whole is nothing but the interrelation of its parts, each phenomenon can therefore be regarded as determining the character of all other phenomena as well as having its own character determined by all other phenomena." (Gregory 1991, 155)

What the examples of ordinary silences and mediality teach us is that no parameter can by itself explain why a particular mode of listening arises. Every parameter is related to every other parameter and creates different kinds of feedback systems to create a phenomenal world that only exists conventionally. All phenomena are dependently originated. As the Sūtra Requested by Anavatapta, King of the Nāgas says:

"Aside from the dependently originated, a bodhisattva does not see any phenomena whatsoever." (Quoted in Mabja Jangchub Tsöndrü 2011, 113)

That all phenomena arise dependently was clearly recognized by the musician Xú Shàng Yíng (徐上瀛) in his Xī Shān Qín Kuàng (溪山琴況)—a treatise on qín playing in which he lists 24 different aesthetic parameters to bring to qín playing. Throughout this treatise, we find that the attempt to outline 24 different virtues as separate topics is thwarted by their dialectical and interdependent nature. In order to explain one, one has to explain another, as when discussing blandness–the quality that I above argued was similiar to ordinariness–in the following quote:

"The sounds produced by all other musical instruments lose their wei 'tastefulness' when they sound placid (dan). However, for guqin music, when the sound of guqin is dan, it creates a kind of tastefulness in the music. What kind of tastefulness? It is tian [恬]…When tian is complete, one does not feel bored with dan." (Tien 2015, 212)

What Xú is getting at here is that blandness (dan 淡) is closely connected to (indeed coupled with) calmness (tian 恬). If the music expresses dan, the quality of calmness is necessarily present. The crucial thing that I take Xú to mean is that blandness is not 'complete' on its own. If blandness does not have the tastefulness of tian, it is just boring and amateurish. Blandness is not enough by itself but needs other qualities to not only complete it but for us to even hear it as 'blandness'.

Furthermore of relevance to the topics of mediality and materiality explored in this text, Xú suggests that for the qín, blandness comes naturally and creates the tastefulness that has the flavor of calmness. The qín itself is an instrument that affords dan. Not any instrument is appropriate for blandness, which means that the qualities of the sounds of the instruments themselves are crucial components in establishing blandness as well. This is obvious since blandness as a musical quality cannot be established without sounds created by instruments. With music for the qín, drawing attention to the instrument itself becomes almost in and of itself a way of establishing blandness. On other instruments, however, other strategies might need to be employed. On these instruments, the successful arising of blandness will have to be explained by even more qualities that are not blandness themselves–perhaps some of the qualities we have mentioned here such as a lack of 'narrative' contrasts.

Xú's way of thinking about aesthetic qualities follows the same structure that we've been exploring in this text. An aesthetic quality like ordinariness is relished when we find a kind of tastefulness in just sounds, and the 'quality' of just-sound-ness (mediality) has to, in turn, be explained by other qualities. In order for sounds to be heard as just sounds, it is not enough to just play sounds. As Lee emphasized above, it takes the special skill of an artist to "transform just what is into just what is" (2018, 251). The sounds have to be of such type that they invite a just-sound-ness. On the qín, these sounds may come rather naturally, but on the piano, it might be necessary to prepare them to give them this quality (as Morton, via Cage, suggests). But it is not only by manipulating timbre that this quality is achieved–the just-sound-ness must be achieved by working with other supporting aesthetic qualities such as non-continuity, non-symbolism, blandness, and here I want to add ordinariness itself. This tautological way of putting it is in keeping with the non-obstruction of sounds and modes of listening explained above. It is just as in a blue painting, the color paint is both the cause and the result. In the same way, ordinariness is in this case both the cause and the result. It is the result of a mode of listening that is about just sound and silence, and it is also the cause of a mode of listening that is about just sound and silence.

In this text, I have been experimenting with postulating qualitative terms like 'mediality', 'aperture', and 'ordinariness'. Maybe these terms can shed some light on Cagean aesthetics; giving something a positive quality is to temporarily employ a heuristic device that might allow us to say something about what we hear. However, what all musical analysis really reveals is that there can be no qualities in sound or silence. The moment we try to define any quality, we see that it slips away. The empty interdependence of phenomena is revealed as we have to define it in terms of some other supporting condition. This continues indefinitely to the point where we see that all word that describes qualities are just ultimately conventional designations. But this lack is only coherent with our experience of these qualities in music. After all, if sounds truly had 'medial qualities', they would no longer be 'just sounds' but rather sounds distorted by conceptuality; if the silences really had indeterminate 'qualities' to them, they would no longer be moments of emptiness.