The 'open' work

John Cage is famous for wanting his pieces and performances to facilitate a mode of listening in which there is no qualitative difference between the sounds produced by instruments and performers—what we conventionally call 'music'—and the unintentional everyday sounds that surround the performance—what we conventionally call 'noise.' Yet, when listening to his music for conventional instruments, as much of Cage's work is, some qualitative and categorical differences inevitably remain. These differences are especially pronounced in a live performance, where the musicians and sound sources are visible and audible. For instance, in One^6 for solo violin, it is immediately apparent what constitutes the 'music' (the violin sounds) and what constitutes the everyday sounds (everything else). Windsor (1995) observes that "the sources of such 'musical' sounds [conventional vocal and instrumental music] are easily identifiable as originating within a specialized cultural domain." Consequently, "such music does not sound like the everyday environment" (136).

If Cage's primary goal had been to completely dissolve the categorical distinction between 'musical' and everyday sounds—if this were a higher priority than, say, creating beautiful pieces—he would have employed different compositional methods and performed in different contexts. He might have taken approaches akin to those of sound artists such as John Wynne or Max Neuhaus, whose works often make it genuinely difficult to distinguish sounds belonging to the 'piece' (typically an installation rather than a concert) from everyday sounds. In these installations, the cognitive act of questioning whether a sound originates from the 'piece,' the surroundings, or even inside the spectator becomes a central part of the experience—a level of perceptual ambiguity that Cage rarely seems to pursue in his compositions.

In this text, I will describe Cage's music as moving toward eroding the distinction between art and non-art—or, more precisely, between the artwork and its surroundings. Although a true non-distinction may never be fully achievable, Cage's music remains remarkably 'open' to its surroundings in a way that is seldom achieved, or even attempted, in much other instrumental art music.

In what follows, I will attempt to elucidate this openness as a feature of particular musical attunements and modes of listening. This sets my purpose apart from writers who have discussed the erosion between art objects and their surrounding worlds on a more general, non-phenomenological level. For example, Jacques Rancière argues that all great works of art are, by definition, 'open' because "genuine art is what indistinguishes art and nonart" (Chow et al. 2011, 44). For Rancière, it makes no difference whether a piece is a land-art object on a shore, destined to be washed away in fifteen minutes, or an 18th-century landscape painting framed in a museum; if it is 'genuine,' it will indistinguish art and non-art. Similarly, Foucault described any book as "not simply the object that one holds in one's hands… and [how] it cannot remain within the little parallelepiped that contains it: its unity is variable and relative" (2002, 25). For Foucault, books are always expansive beyond their edges, regardless of content: it matters little whether a text is a poem designed to draw attention to the font in which the words are set and the paper upon which it is typed, or if it contains the kind of writing that calls for the reader's complete absorption in a narrative flow, making her forget the pages she turns. In this context, we can also recall Heidegger—whom we will meet again later—who saw artworks as peculiar moments in which a kind of strife between an artwork’s thingness and the surrounding world occurs, with artworks possessing a strong world-creating purpose. For all these thinkers, art always involves ways in which the art object is, in some sense, 'open' to its surroundings.

We can agree with these philosophers that, ontologically, the open and relational nature of art is always true. All experiences, subjects, and objects are mutually interdependent, and ultimately, it does not make sense to speak of discrete objects or isolated experiences. From the Buddhist perspectives that inform this writing, everything is empty and relational. This line of reasoning is important in itself, and I will return to it later when discussing aesthetic 'qualities' in music. In particular, the qín musician Xú Shàng Yíng, in his treatise Xī Shān Qín Kuàng, lists twenty-four aesthetic qualities—but the attempt to treat these 'virtues' (as he calls them) as distinct topics is constantly thwarted by their relational and interdependent nature. Individual qualities cannot be pinned down or assigned to any single sound; they are always constituted through their relations. Just as we cannot define precisely what makes a 'book,' the actual quality of music constantly eludes grasp. From this ontological perspective, any 'piece of music' is, by definition, open to its surroundings; trying to delineate its edges as something separate is, as Madhyamika thinkers have shown, ultimately illogical.

Contrary to this ontological approach to the idea of 'the open work,' I am interested in how erosions between art and the everyday appear within the experience of listening to certain pieces of music. Ontologically speaking, all works may be open. Phenomenologically speaking, they may not. Foucault is right that all art experiences are contingent upon, open to, and inclusive of phenomena beyond the work. Yet one kind of art may feel like an 'isolated event', while another may feel more 'open' to its external environment. Beyond capturing this openness phenomenologically, I am also interested in it from the perspective of poetics. From our listening experience, we know that certain modes of listening are more 'open' to the outside than others—but what features of the works make this possible? How do musicians and composers bring this about? I am interested in unpacking the affordance structures that enable such erosion.

When I speak of a piece's 'openness,' I am not referring to a distinction between realism and fiction in the content of an artwork, but rather to differences in how its medium appears. In music, however, an aesthetic quality of 'realism'—using sounds that might naturally occur in everyday environments—is not irrelevant to the openness I will be discussing here. As we will see, the use of such 'found sounds' can lessen music’s sense of belonging to "a specialized cultural domain" (Windsor 1995, 136) and thereby open it to its surroundings. Yet it is important to emphasize that this aesthetic quality of realism is by no means required for openness to arise.

Furthermore, the 'openness' I am describing is not the same as that intended by Bourdieu, Eco, and Nattiez in their discussions of openness in art. For them, openness lies in how art allows for a plurality of signifieds by being "intrinsically and deliberately polysemic" (Bourdieu 1984, 3). In this sense, openness refers to interpretive freedom—an unfixed or 'open' meaning. Yet, as with the idea of found sounds mentioned above, this dimension is not irrelevant to the openness I'm interested in here. One of Cage’s primary techniques for cultivating the kind of openness I am interested in was to strip away symbolism, narrativity, and musical emotion so that sounds could be heard simply as themselves. As we will see, when sounds are heard as mere sounds, they become transparent and open to their surroundings. But these mere sounds are not barren or clinically pure phenomena; they become fertile sites for various leaps of the imagination of, what Kant called, the mind's free play. In this way, such sounds are 'intrinsically polysemic.' Thus, the polysemic openness described by Bourdieu, Eco, and Nattiez is related to, though distinct from, the openness that will be the focus of this text (see also LaBelle 2006, 9–10).

The 'virtual' world

As we have seen above, openness in music can refer to many different qualities. In order to pinpoint the kind of openness that Cage was interested in, which is the focus of this text, it is useful to understand what musical practices he was reacting against. Simply put, Cage resisted the idea that music must function as what DeNora (2000) called a "virtual reality" (157). A romantic symphony is such a virtual reality because it establishes itself as a world different from the world in which it is performed. When a romantic symphony is performed, the entire acoustic field of phenomena is divided into one layer of what Ihde (1990) called a "smooth tonality", which is affirmed, and another layer of noise, which is rejected. As Erik Wallrup (2012) describes in his phenomenology of musical attunement, the listener of a romantic symphony is drawn into a virtual world distinct from everyday life:

"In the phenomena of musical attunement, the temporality of the music is the temporality of the listener, and that accounts for the spatiality, mobility, and materiality too. When something around the listener intrudes, when he becomes aware of someone making a noise in the audience, when the light in the concert hall is changed, or a person starts to walk around, then the spell of the attunement runs the risk of being broken. The listener is not in the everyday world, but in the world of the musical work, a world without time and space, but with temporality and spatiality, with mobility and materiality. The listener does not identify himself with the work, because the identification can only be made when there is a distance between subject and object from the start; he does not let himself sink into the music in an empathetic act, since the subject in that case has to move itself in a specific direction. Both alternatives call for a reflection or at least an intentional act, which is incompatible with the attunement." (Wallrup 2012, 233)

If Ihde's separation of a "smooth tonality" and noise seems like a cognitive act of classifying sounds as either 'music' or 'non-music,' Wallrup's perspective emphasizes how this dualism manifests from an attunemental point of view. When we are thrown out of the virtual reality of music, it is not as if 'dirt' (e.g., noise) has suddenly been thrown onto the 'smooth screen' of tonality; rather, the outside noises simply do not make sense with the materiality, mobility, temporality, and spatiality of the musical attunement to which we are nondually attuned when listening—that musical attunement that we simply are. Music listening is not, as DeNora (2000, 157) wrote, a matter of "abandon[ing], albeit temporarily, the realm of material and temporal being," but rather of being attuned to a musical world in which a different material and temporal being takes hold. From this perspective, Cage's music was not about creating a screen onto which both dirt and purity could coexist, nor about categorizing sounds so that all sound types are considered 'music.' Instead, it was about cultivating a fundamental attunement—a world—where the materiality, temporality, mobility, and spatiality of the everyday could be present within the musical attunement itself.

If we define Cage's openness from this attunemental perspective—where the goal is to create a porous, transparent attunement that does not exclude the materiality, mobility, temporality, and spatiality of whatever indeterminate ambient phenomena may occur in the space where a piece is performed—this definition still does not fully capture the kind of openness Cage's music achieves. Composers associated with the acoustic ecology movement, for instance, created outdoor pieces in which the sounds of nature literally became part of the music, and their works could also be said to fit this definition. Cage's approach, however, was different: his music was not merely about ambient sounds becoming music, or music becoming ambient sounds. While this might have been his intention with 4'33", his later pieces—which I take in this text to be paradigmatic of his approach—establish a different kind of relationship between music and ambient sounds. In his later works, Cage welcomed everyday phenomena into the experience without transforming them from their status as primordial indeterminacy—that is, without turning them into musical objects. In other words, the musical attunement was open to coexisting with ambient sounds, but it did not colonize them; it did not incorporate them into the musical syntax in the way that some outdoor pieces by acoustic ecology composers attempt to.

Transcending emotions

When listening to Cage's late Number Pieces, the Cage interpreter Rob Haskins describes the feeling of the music increasingly "taking equal precedence" with the other events around him. It is "gently enveloping" him until he perceives "minute details of everyday life with a fresh, uncluttered clarity." To this, he adds a statement expressive of wonder: "Perhaps this experience transcends any emotional reaction I could have" (n.d.). In his sensitive writings, Haskins illustrates how Cage's late music manages to integrate with everyday sounds to some extent—"more and more," but never fully indistinguishable from them—and how this yields a meaningful aesthetic experience ("transcends any emotional reaction I could have"). This passage by Haskins is in harmony with my own approach to Cage's music: the purpose is not for the music to 'become' the environment, but to bring about a changed relationship to it—to see it with a "fresh, uncluttered clarity." This changed relationship is not achieved by fully submerging the music in the environment, but rather by gently intimating it through sound.

It is, therefore, a mistake to claim that all there is to Cage's music is an intention to create situations where sounds 'just happen', where all boundaries between 'art' and the everyday are eroded, or where the music sounds exactly like the everyday environment (since a violin obviously does not). LaBelle emphasizes this point, writing that Cage's music "initiates a conversation in which the musical and found sounds merge, making music a cultural paradigm beholden to sound and its situatedness" (2006, 21). For there to be a conversation, however, the musical and found sounds cannot merge completely. Cage understood that musical sounds could never be perceived as the 'just sounds' of the ambient environment—and that was never the point. Rather, the goal was to use music to open up poetic encounters with ambient sounds: the kind of profoundly meaningful encounters Haskins describes as transcending any "emotional reaction".

The music as a process

Contrary to the idea of a musical piece as something autonomous that can be 'moved around', Cage's music was to be perceived as inseparable from the time and place in which it was performed. Cage therefore referred to his own music as a process rather than an object. Unlike an object, a process is not something one can simply 'drop into' a given time and place; it necessarily becomes part of the spatio-temporal flow, while, in Cage's case, still remaining recognizable as 'music'. In Cage's processes, a distinction remains between the musical sounds and the everyday environment, yet both coexist within the same unfolding process.

Because of Cage's goal to create art that does not isolate itself from its surroundings, there is a strong connection between his music and the aesthetic concerns that motivated the emergence of site-specific art in the 1970s. Like Cage's compositions, this art seeks to replace the "pure idealist space" of modernism with "the materiality of the natural landscape or the impure and ordinary space of the everyday" (Kwon 2002, 11). Most of Cage's late pieces are not site-specific in the strict sense, but they possess a porousness and adaptability that allow them to be performed in different kinds of spaces, while always bringing the space and its sounds into the same process as the music. This is similar to the sculptures of Lee Ufan, a leading artist working with site-specific installations. The basic structure and elements of his pieces are pre-determined, but allowing the exact placement and configuration of their elements to be malleable, and working with empty space, enables the works to feel site-specific. Because of the clear connection between Cage's music and Lee's art, and because Lee's writings on this process are so detailed and insightful, I will draw upon them later in this text to help elucidate aspects of Cage's music.

The difference between processes and objects was introduced by Cage in a discussion about silences. Regular Western music–objects–had 'musical silences', but Cage's music–processes–had 'ordinary silences'. Cage included among objects even some of his own early pieces. The silences in them were similar to the silences in Western classical music–the kind of silence that makes the music perceived as an object rather than as a process. Even though he approved of the noticeable inclusion of silences in his early pieces, the silences were too dramatic and pregnant with energy. Such silences close the piece down and prevent them from opening to the everyday; they lack the quality of ordinariness.

To some extent, I agree with Cage that his early silences feel somewhat more dramatic, but I personally find some of them to be open as well. I am thinking here of the first long silence in the first movement of Two Pieces for Piano (1946). I remember very clearly the first time I heard this silence and how the emptiness of ordinariness was revealed to me therein. Even the gorgeous silences in Four Walls (1944) are worth mentioning. Although these silences are often preceded by short attacks—it is not the case that they arise from sounds simply fading away—this does not, for me, imbue them with the kind of strong anticipation that would transform them into 'musical silences'. It is certainly true, however, that they do not possess the serene ordinariness found in the silences of, for example, the Number Pieces.

Cage famously said that "there is no such thing as silence" because the background noise of the everyday is always present. Francisco López (1996) challenged this Cagean axiom, arguing that silence does, in fact, "exist; in music". What it means for silence to exist in music is that the quality of the silence is such that the everyday noises are not allowed to be present—they are simply 'ignored' by the categorizing mind. Not consciously, but attunementally. It seems, however, that López overlooked that Cage had already addressed this critique in an interview with Jonathan Cott, in which Cott makes a similar remark by pointing out that musical silence is opposed to ordinary silence "because it is created within the framework of the composition by that first sound" (1963).

Because musical silence differs from ordinary silence, we can, according to Cott and López, say that silences exist in musical listening, and hence that there is such a thing as silence. Their argument is phenomenological: scientifically measured, there might always be background sounds happening, but if we do not hear them because of the mode of listening we are musically attuned to, they are not there. Cage's reply was: "Certainly if we are speaking about objects, you see." Here, Cage introduces the distinction between objects and processes. Contrary to the pieces of the classical standard repertoire (objects), Cage creates processes in which the "framework of the composition" that Cott mentions does not appear. Rather than closed structures, these are perpetual states of becoming. The kind of framework—or the 'strong' musical worlds that Wallrup has in mind—is absent. Because these processes are continuous with everyday life, Cage's music has 'ordinary' silences instead of 'musical silences'. Therefore, in Cage's pieces, musical silences, in the way Cott and López use the term, do not exist. Cage agrees with Cott that 'musical silences' exist in other music, but not in his own. So when López argues that there is silence in music, he would be correct for most modes of listening, but not for the one that Cage was trying to attune us to.

Different kinds of silences

An anecdote recounted by Brooks (2010) problematizes, in a revealing way, the idea that all silences in Cage’s music are ordinary silences. During a performance of Cage's violin solo Freeman Etudes by Paul Zukofsky, with the composer present in the audience, a creaking door disturbed the hall. Yet no one dared to close it, since they knew of Cage’s conviction that no distinction exists between environmental and musical sounds. The audience likely recalled the story Cage often retold about Christian Wolff, who would play the piano with the windows open so that the sounds of traffic often washed over the music, at times rendering the piano inaudible. For Cage, Wolff’s attitude was exemplary:

"One day when the windows were open, Christian Wolff played one of his pieces at the piano. Sounds of traffic, boat horns, were heard not only during the silences in the music, but, being louder, were more easily heard than the piano sounds themselves. Afterward, someone asked Christian Wolff to play the piece again with the windows closed. Christian Wolff said he'd be glad to, but that it wasn't really necessary, since the sounds of the environment were in no sense an interruption of those of the music." (Cage 1967, 133)

At the Zukofsky concert, Cage eventually got up and adjusted the door to stop the noise. Later, during the post-concert Q&A, he was asked about this incident and defended his choice by describing the Freeman Etudes as follows:

"What you have is an extremely complex situation, like poetry condensed in time. You have only a brief moment to hear a very complex situation which, it is true, is open to noises; but I don't want to hear them because I don't know these pieces very well yet and I don't have very many chances to hear them” (Brooks 2010, 61).

It seems as if Cage is suggesting that, since he had not yet familiarized himself enough with the piece to 'let it be open,' prior familiarity is a necessary condition. If this were true, then attempts to locate the capacity for music to open in the affordance structures of the composition itself would be undermined: what determines whether a piece can open would instead reside in the listener—whether they are familiar enough with the work to allow it to open. The distinction between 'musical silences' and 'ordinary silences' would then not be a property of the compositions themselves, but only of different listeners' knowledge and experience. For the claim that openness or ordinary silences arises from the music itself to hold, the music must open spontaneously, without dependence on prior listening or degrees of familiarization.

At the same time, I agree with Cage that the Freeman Etudes are exceptionally complex pieces requiring intense, concentrated attention, and for this reason, they are not representative of the kind of open works I am discussing here. Despite being composed by Cage, and despite his need to defend them as 'open' to support his ideas, his act of closing the door suggests otherwise. The Freeman Etudes might even afford what could be considered musical silences. Haskins, for example, almost exclusively attributes the quality of openness and ordinary silences to Cage's Number Pieces, which are slower, less dense, and lack the energetic gestures characteristic of the Freeman Etudes.

It is therefore important to recognize that different pieces—even when written by the same composer—call for different enactments of silences; not all of Cage's music, for example, calls for 'ordinary silences'. A similar idea is expressed by Jürg Frey in an interview. As a 'Wandelweiser' composer, he is often asked whether ambient noise is acceptable during the silences in his music. His response reveals that the answer depends on the piece:

"That’s an interesting question. I have silence in a lot of my pieces, and the answer to the question isn’t the same for every piece. In my String Quartet No. 2, for example, I think it sounds best when it’s silent; when the audience is concentrated. They can be sitting or lying down on the floor or whatever, but there shouldn’t be additional distractions. No sandwiches to eat during the concert, and no walking in and out. It’s 30 minutes, and you should just try to concentrate. Of course your mind wanders—that happens to me too. It’s not like I listen to the piece and for 30 minutes I’m completely concentrated on every note. That’s totally normal. That might be less true for other pieces of mine. If they’re longer, or if they have more silence, then it’s worth considering whether the performance situation should be different. But for the String Quartet No. 2, concentration matters." (Brown 2017)

Frey’s words remind us that silences are not uniform but unfold differently in each composition; much like Cage, he shows that 'ordinary' silences emerge only when the music, the space, and the listener converge in a particular attunement.

Just sounds

The question then becomes how Cage produces ordinary silences in some of his pieces. The answer is not easily found in the silences themselves, since their perception depends so much on the surrounding sounds and they have little 'say' over their own reception. To claim that Cage achieved ordinary silences simply through his use of silence would be tautological, like saying that a patch of color is red because it is red. What we can see, however, is that lengthy silences seem to be a recurring motif in ordinary silences. In a particularly compelling listening experience described later in this text, Cage notes that the silences are "extremely long." Yet the significance of these silences lies not in their duration per se, but in how such expanses of silence affect the musical flow: extended silences force the music to repeatedly 're-start,' generating a constant sense of beginningness—a quality that, in what follows, I will call the aperture of the music. Thus, the search for ordinary silences leads not into silence itself, but into the sounds that surround and frame it.

Having considered silence, we must therefore turn to sound. As already noted, Cage aims to produce sounds that neither dissolve into the ambient environment nor retreat into a closed, virtual world. His goal is to make a work of art that remains open—transforming the audience’s encounter with its surroundings without the art being completely submerged in it. In this sense, the sounds function as mediators, a term introduced by Lee Ufan. In discussing his sculptures, Lee articulates a vision that parallels my reading of Cage’s music, in which art seeks to situate itself between virtuality and environment:

"A work of art can neither become an idea as such nor reality as such. It exists in the interval between idea and reality, an ambivalent thing that is penetrated by and influences both. My work is not the creation of modernist totalities or closed objects. It is important to create a stimulating relationship between what I paint and what I do not paint, what I make and what I do not make, the active and the passive. […] That is, by limiting the act of making and combining it with things that are not made, I incorporate externality and reveal a non-identified world. [...] Just as humans are physical beings, points of contact between internal and external worlds, works of art must be living intermediaries that mediate between and exalt the self and the other." (2018, 51)

Like Lee’s sculptures, Cage’s sounds occupy this interval: they are not simply "reality," the ambient environment, nor "ideas," sealed-off musical objects, but mediators that reveal both the work itself and the world around it.

Lee was deeply influenced by Heidegger, and in his notion of mediators one can sense the imprint of Heidegger’s idea that artworks are sites of strife between the non-objective world and the artwork’s material presence, or "earth." In an evocative passage, Heidegger distinguishes between the mason and the sculptor: both use stone, but what makes the sculptor an artist is that "he does not use it up." The same applies to the painter: "the painter also uses pigment, but in such a way that colour is not used up but rather only now comes to shine forth" (Heidegger 1971b, 46). Echoing this thought, Lee writes that "[t]he task of the artist is to transform just what is into just what is" (2018, 251). To transform the material of art into just what is—by allowing the thingness of the work to shine forth—is precisely how openness emerges, because it brings into the experience both the non-objective world and the material presence. As Heidegger puts it, "The setting up of a world and the setting forth of earth are two essential features in the work-being of the work. They belong together, however, in the unity of work-being" (1971b, 46).

What makes Lee’s approach unique, however, is that while the "world" for Heidegger is what we might, in Buddhist terminology, call a saṃsāric world—the horizon that renders human life intelligible and meaningful to persons (Skrt. pudgala)—the exteriority that Lee’s art opens up to is the dharmakāya (Lee 2011, 112): emptiness itself. The "non-identified world" is thus not, as in Heidegger, the background practices that make up a culture, but rather the field of indeterminacy from which phenomena emerge as emptiness.

For the art to function as a mediator, there must be a balance between openness and constraint: the work must fuse with the world "while remaining separated from other things" (2018, 251). Lee writes:

"[t]he act of simply pointing to a rock on a river bank might be called a work of art. In such a case, however, the limitations placed on the stone might be too slight, and there is a danger of the work being completely submerged in nature." (Lee 2018, 251)

In other words, if the work is too open, it will no longer perform its function to open. "On the other hand," Lee continues, "if I work on the stone and carve it into a human figure, the constraints placed on the work are too strong and there is a danger that it will be totally closed off from nature" (2018, 251). The art would then start to function like autonomous objects that do not invite to anything but the act of ignoring its surroundings.

Lee's description can be transposed to the analysis of Cage's music: the sounds of musical instruments act as 'mediators' between the music and the indeterminate emptiness surrounding it. These mediators make present the openness of the "non-identified world" without making it identifiable as something. For this to occur, the music cannot attempt to sound exactly like the ambient environment. Instead, it must form a "contradictory structure" that is "simultaneously unified and divided" (Lee 2018, 251). As LaBelle (2006) notes, the musical and found sounds must both be in a conversation and merge–they must be simultaneously divided and unified.

An example of music that is too closed to open is the Romantic symphony, which creates its own virtual reality and excludes ambient sounds because they do not belong to the world of the music. Conversely, an example of music that is too open for emptiness to preside is Cage's own 4′33″. This piece lacks mediators entirely: it is completely silent, and the ambient sounds that appear in this silence do not possess the mediality necessary to function as mediators. Paradoxically, the ambient sounds instead become the foreground of the piece, turning into objects of attention—which, as noted above, was precisely Cage's intention with 4′33″. In this case, then, we do not hear silence as emptiness. By contrast, in Cage’s Number Pieces, the instruments provide precisely the kind of mediating sounds that allow emptiness to emerge without being objectified, exemplifying the delicate balance between openness and restraint that 4′33″ lacks.

Building on this insight, it is important to note a crucial difference between Lee’s conceptualization of mediation and LaBelle’s interpretation of Cage. While LaBelle frames Cage’s musical sounds as mediators between musical and found sounds, Lee’s approach—applied to Cage’s poetics—suggests that the musical sounds act as mediators between musical sounds and emptiness itself. The difference is that emptiness is a "non-identified world" and indeterminate, while the found sounds are simply the sounds that occur in the environment–sounds that can become the object of focus. The way I read Cage, and why Lee is a good explicator of his music, is that the purpose of the musical sounds is not to make us hear the ambient sounds. Instead, they aim to generate encounters with indeterminacy. For this to happen, the ambient sounds are neither ignored nor made into foregrounded objects of perception. When Cage describes an ideal musical experience as being like "not listening to music" and as just being about experiencing how "sounds simply happen" (1981, 119), I do not interpret Cage as actively hearing ambient sounds as objects–as if listening to the sensuous sounds of a field recording–but that he was letting phenomenality arise as emptiness–not listening to anything but also not ignoring anything. It is the indeterminacy of the situation that is relished, not so much the 'found sounds' that the ambient field provides. It is in this activity of non-selective, open awareness that we find a connection between the mode of listening to Cage's music and the meditation style of Zen, something we will explore more below.

The way in which Cage makes his sounds function as mediators is by giving them a medial quality. When music ‘hides’ its medium behind an obscuring ‘veil’ of sound, it creates an artificial dualism between the music and the rest of the phenomenal field. Romantic orchestral music, mentioned above, provides a clear example of this. Such music constructs veils that obscure the transparency of sound by conjuring 'musical illusions.' These veils produce a phenomenological separation—not only between musical sounds and ambient sounds, but also between the "smooth tonality" (Ihde 1990) and the noisier aspects of the sounds produced by the instruments themselves. As Scruton (2009) suggests, the nature of sounds is already, in a sense, insubstantial and illusory—they are like rainbows or echoes—but Romantic music conceals this basic illusoriness by transforming sounds into entities distinguished from the full phenomenal field. It is akin to carving a realistic human sculpture from natural rock: the shape of the rock is given expressivity and meaning, a life of its own. Yet in doing so, the sculpture both hides its material and stands apart from the surrounding environment as something discrete. One strategy to avoid such phenomenological separation, therefore, is to draw listeners' attention to the sounds themselves—to just sounds, to just what is. When sounds direct attention to themselves in this way, they acquire a medial quality.

In Ecology without Nature (2007), Morton describes how mediality necessarily performs a kind of 'ambient poetics': it conjures or brings to life the atmosphere—the ambiance—surrounding the artwork. Moments of mediality always carry a dual property: they are both self-reflexive (sound is just sound, not striving to be something else) and simultaneously open to their surroundings. The medial quality reveals that music is composed of the same 'stuff' (that is, sounds) as everyday life, and therefore does not create a disembodied 'virtual world' apart from it. By making the medium itself the focus of art—by drawing our attention to the details of sound—the transparency of sound is revealed. Mediality, then, necessarily implies that sounds function as 'mediators' in Lee’s sense introduced above: sounds that are medial become mediators between the created and the uncreated.

In Ecology without Nature (2007), Morton uses the violin to illustrate the quality of mediality. A medial musical passage for the violin, they write, is one that makes us "aware of the violin-ness of the sound—its timbre" (37). Morton leaves the point relatively undeveloped here, but in subsequent works—The Ecological Thought (2010) and Hyperobjects (2013)—they expand the idea of instrumental music in which the very 'content' of the music is the sound of the instrument itself. There, Morton emphasizes that such musical sounds lack the character of being merely "materials-for (human production)" (2013, 172). Rather than serving as expressions of human emotionality or the inner lives of composers, the sounds are allowed to resonate on their own terms:

"Gradually the inside of the piano freed itself from embodying the inner life of the human being, and started to resonate with its own wooden hollowness” (2010, 165).

One composer Morton singles out as central to this shift is Cage. "Cage’s prepared piano makes us aware of the materiality of the piano, the fact that it is made of taut vibrating strings inside a hard wooden box" (2007, 38). With his prepared piano pieces, Morton argues, Cage was the first composer to free himself from ego and begin truly listening to the instrument. Rather than writing sounds to voice his inner being, Cage gave sounds their own "anarchic autonomy" (2013, 165). Admittedly, Morton here conflates different stages of Cage’s career: the Sonatas and Interludes for prepared piano were composed during a period when Cage was interested in embodying through music the eight "permanent" emotions of Indian rasa theory—the humorous, the wondrous, the erotic, the heroic, anger, fear, disgust, and sorrow (Kostelantz 2003, 67)—while the idea of sounds as autonomous points in a field of anarchy belongs more to his later works, such as the Number Pieces. Still, Morton’s broader claim holds: by attending to the materiality and autonomy of instrumental sound as content in itself, we hear sounds in their uniqueness and as-is-ness. They no longer function as faceless sources for acousmatic veils or as vessels for human emotion, but instead disclose themselves directly.

The way I understand Morton’s theory is that sounds become "just sounds" when we refrain from imposing human emotions, intentions, or narratives onto them. We should neither manipulate sounds into expressive vehicles nor treat them as mere "materials-for" production. At times, certain sounds—by virtue of their unique timbres—seem almost naturally to draw attention to themselves. In Cage’s prepared piano, for instance, the inherent noisefulness, complexity, and heterogeneity of the timbres readily direct our listening toward the sounds themselves. Yet mediality is not inherent in any sound: it is primarily a matter of compositional articulation. Any sound can be heard as "just sound," just as music for prepared piano can fail to draw attention to the sonority of the instrument.

Cage’s strategies for achieving mediality were essentially strategies of negation—acts of withholding many of the devices conventional music employs. Mediality arises when qualities such as continuity, symbolism, and narrativity are suspended. None of these qualities, however, belong to sounds in themselves; it is the musical context—the relation of one sound to those preceding and following it—that determines whether it is heard as symbolic, narrative, or non-symbolic. The crucial point, as Morton emphasizes, is that when music no longer functions as a representation of human emotion, it can begin to sound like a collection of just sounds. Mediality, then, is not a property of sounds themselves but the effect of compositional practice. It names the mode of listening that emerges when conventional strategies are negated. We cannot, therefore, say that using just sounds is itself a strategy for achieving Cage’s mode of listening; rather, "just sounds" describes how music is heard once other qualities—or the negation of qualities—have been put into play.

Aperture and beginningness

As noted above, sounds that possess a medial quality are both self-reflexive and open to their surroundings. Mediality is not simply about directing attention to sounds in order to enhance detailed listening; it is about creating a situation in which sounds become open to the environment around them. Morton writes that the medial "undermines the normal distinction we make between medium as atmosphere or environment—as a background or 'field'—and medium as material thing something in the foreground," aiming to "undermine the normal distinction between background and foreground" (2007, 38). Medial sounds thus function as mediators between musical sounds and their surroundings. As contradictory structures (Lee 2018, 251), they embody aspects of both background and foreground simultaneously.

While openness is a defining feature of mediality, Morton identifies an even more specific aesthetic quality that captures what happens at the boundary between the artwork and its surroundings: aperture. Whereas mediality draws attention to the sounds themselves, aperture emphasizes their edges—the points where the work opens onto the surrounding world. Speaking of an artwork’s aperture conveys the experience of clearly perceiving its 'beginnings' and 'material edges'. By contrast, a frame around a 19th-century landscape painting does not produce aperture; the frame merely separates the painted landscape from the wall, creating a window into a different, self-contained world. Morton analyzes aperture as a crucial aspect of minimalist painting and sculptural practices, where frames are often absent:

"Where does the work of art begin if there's no frame around it—and if the work is only a frame with a blank, we are left with the same question" (2010b, 38)

When the aperture of sounds is clearly manifested, it becomes impossible to experience the music as a self-contained virtual world. Worlds, by definition, are all-encompassing: they are environments one simply inhabits, navigates, and takes for granted, without having to reflect on them. They are not discrete objects but referential wholes in which individual objects can emerge. A pronounced sense of aperture, however, directs attention to the beginnings and edges of the music, making it difficult for the piece to establish a separate, immersive world apart from the everyday environment.

Takemitsu (2004) recounts an experience that illustrates how the quality of aperture can extend music into its surrounding environment. While dining with a shakuhachi musician, the musician performed a piece during the meal. The shakuhachi, like Cage’s prepared piano, naturally draws attention to its materiality: its complex timbres, heterogeneity, and inherent noisefulness encourage detailed listening. The instrument’s honkyoku repertoire exemplifies this, with frequent silences that heighten the listener’s awareness of the interplay between the sounds of the flute and the surrounding environment. In this context, the contact between the shakuhachi and the ambient sounds—such as the sizzling of sukiyaki—becomes an integral part of the music’s 'content.' At times, Takemitsu found himself more attentive to the ambient sounds than to the flute itself. The musician, however, interpreted this as a sign of a successful performance: "then it is proof I played well" (2004, 201), rather than as an indication that the performance was dull or distracting.

A similar observation is offered by Cage, though from a slightly different perspective:

"I remember, when I first got involved with studying Zen Buddhism, loving those stories that came from a shakuhachi player who was also interested in cooking. The sound of the music continued in the cooking!" (Cage & Oliver 2006)

In both Takemitsu’s and Cage's accounts, the performance not only draws attention to the materiality of the instrument but also heightens awareness of the surrounding environment. This interplay demonstrates how the qualities of materiality, mediality, and aperture work together to erode the conventional distinction between music and its environment.

Importantly, this effect does not depend on the presence of cooking sounds or any particular ambient element. It would be a mistake to interpret these anecdotes as suggesting that the boundary between music and the everyday is erased only because the shakuhachi "continues" into the food. Cage is not an acoustic ecology composer who sees any value in trying to harmonize the musical sounds with say, the sounds of nature. Rather, the sizzling sukiyaki provides a concrete illustration of the kind of unpredictable associations between musical and ambient sounds that might happen precisely because the music is open. The spectral qualities of sizzling sukiyaki resonate with those of the shakuhachi, allowing the music to extend into the cooking and for the cooking to be part of the music. Silences and pauses leave space for ambient sounds to interact with the musical sounds. Even when unintended by the composer, the music’s openness creates possibilities for unpredictable, free associations between environmental sounds and the music, even allowing these external sounds themselves to function, together with the musical sounds, as mediators between sound and emptiness.

If the above discussion of aperture focuses on the edge where sound gives over to ambience, the quality of aperture also draws attention to the 'beginning-ness' of sound, highlighting how it emerges from the ambient field. Because aperture, sounds do not create an exclusive, self-contained 'world' of their own but rather remain transparent. In his discussion of the phenomenology of Stimming, Wallrup identifies this quality—the 'endless beginning' or the 'beginning that never starts'—in the music of Giacinto Scelsi:

"Even more radically, pieces like Giacinto Scelsi's Quattro Pezzi per Orchestra (ciascuno su una nota sola) never begin. They are pieces of becoming, not of being. They open up spaces that never reach the status of world-hood; they never leave the phase of tuning-in since they never reach into anything, always standing on the threshold of something that is never made present." (2012, 314)

From Wallrup’s perspective, this quality may appear as a deficiency: the music fails to construct an immersive world. However, such a reading misses the point. By emphasizing becoming rather than being, the music opens onto a vaster space beyond any self-contained musical world. In this way, the edges and beginnings of the music invite encounters with the empty ground from which all phenomenality arises, allowing the music and its surroundings to merge. Here, the distinction between Lee’s conception of externality and Wallrup’s Heideggerian approach becomes clear. For Wallrup, music is judged by its capacity to create a meaningful world, so critiquing Scelsi’s pieces for never reaching "the status of world-hood" follows naturally. For Lee—and, by extension, Cage—externality instead opens toward emptiness. From this perspective, the refusal to achieve 'world-hood' is not a flaw but precisely the point: by remaining in becoming rather than being, music can more directly intimate emptiness, enabling the listener to relish the nonduality between, for instance, the sizzling food and the shakuhachi sound, and to experience emptiness as it manifests in varying auditory forms.

An aesthetics of ordinariness

Noël Carroll described Cage’s music as expressing a “new aesthetic category” of ordinariness (1998, 128). This modal term captures how Cage’s music seems to exist in this world rather than in some fictional or virtual space. Instead of being carried away from ordinariness by music, Cage wanted to be “transported … to [his] daily life, when [he is] not listening to music, when sounds simply happen” (1981, 1119). Daily life contains infinite moods and feeling states, but the qualifier "when sounds simply happen" points to a kind of detachment and non-involvement: the sounds arise without involvement or reaction. It is not about being swept up in sound or hearing it passionately, but about hearing with equanimity—hearing sounds as simply happening. To speak of ordinariness in Cage’s music is therefore to name an affective quality with which the music is open.

As Haskins makes clear in the quote above, the mood of ordinariness that Cage’s music attunes him to is different from the kind of ordinariness that Kenneth Goldsmith (2004) describes in his aesthetics of boredom—though such a view has been predominant in the reception of Cage's work (see Jaeger 2013, 82). Cage’s ordinariness does not lead to boredom but to a kind of clear seeing of the everyday, free of strong emotional reactions. As an affective mood, I take ordinariness to be not too dissimilar from what the Chinese aesthetic tradition calls blandness (淡): the unimposing flavor said to taste like water. Like blandness, ordinariness has an extremely subtle taste. It feels more like an attunement to everyday life rather than an attunement to a musical world. It is partly because sounds carry no charged affects that they can arise in this way as just sounds—as simply what is. In this mood of ordinariness, we relish the tastefulness of sounds stripped of their conventional musical functions and flavors.

Descriptions of Cage’s daily life often had a distinctly meditative quality. Cage never described himself as a meditator—in fact, he sometimes seemed to deride formal meditation, referring only to the 'unusual' posture of sitting cross-legged—but he consciously described his everyday life as full of mindful activities, such as watering the hundreds of plants in his apartment (1990). Cage's apparent derision of formal meditation and simultaneous praise of practical activities parallels Chán iconoclasticism, in which a simple wood chopper may be more awakened than a meditating monk, and where "eating when hungry, sleeping when tired" constitutes more of an awakened activity than meditating in the meditation hall. Beginning in the Tang dynasty, Chán texts described ordinary daily activities—wearing clothes, eating, carrying water, drinking tea, chopping wood, washing bowls—as expressions, manifestations, or functions (作用) of the essential nature (性), or Buddha nature (Jia 2006, 82). While Cage did not practice meditation, he emulated its discipline, approaching his composition practice with a rigor akin to zazen:

"Rather than taking the path that is prescribed in the formal practice of Zen Buddhism itself, namely, sitting cross-legged and breathing and such things, I decided that my proper discipline was the one to which I was already committed, namely, the making of music. And that I would do it with a means that was as strict as sitting cross-legged, namely, the use of chance operations, and the shifting of my responsibility from the making of choices to that of asking questions." (Cage in Kostelantz 2003, 42)

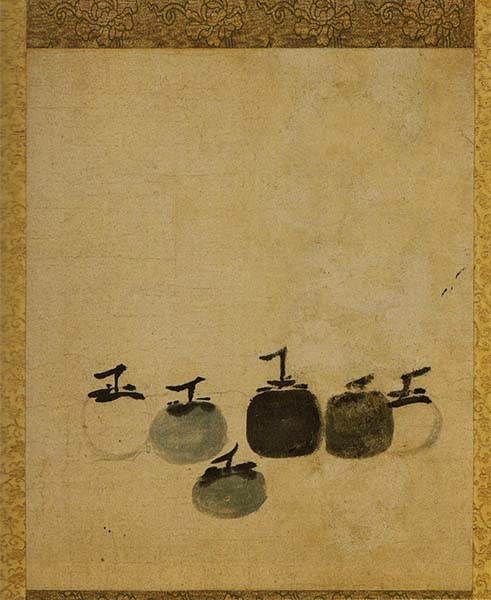

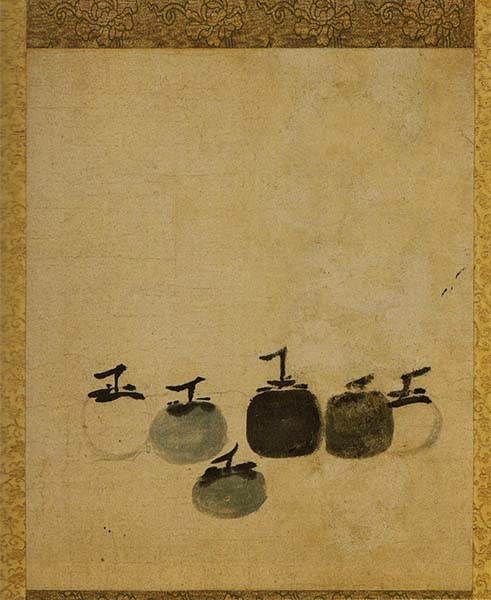

I read Cage’s wish to be transported to "daily life" against the backdrop of Chán iconoclasticism and its valorization of ordinary activities as already awakened. Cage did not seek to be transported back to the oppressive drudgery of office life or to the sense of ennui often associated with mundane tasks. Nor does he aim for the Goldsmithian boredom sometimes attributed to his music. Rather, the ordinariness Cage evokes is the 'awakened everydayä that he often evoked when talking to journalists: a state in which ordinary acts and sounds are experienced with attentiveness and equanimity. His compositions, like the Chán paintings of Muqi, are "fit for a monk’s quarters." Just as there is nothing explicitly 'Zen' about everyday objects such as Muqi’s six persimmons, there is nothing 'Zen' about Cage’s music, but both artists succeed in conveying a fresh perspective on reality-as-Mind and attuning their audience to an actualization of ordinary life as already awakened. They transmit many of the same qualities cultivated in meditative practice: Cage’s ordinariness carries the equanimous perspective of hearing sounds as 'just sounds simply happening,' embodying the kind of mindful awareness cultivated in monastic settings. This is the everyday to which Cage wished to be transported.

This emphasis on the ordinariness of daily life can also be situated in a broader cultural context. In the West, the affirmation of everyday life has roots in historical developments such as the European Reformation. Taylor (1989) traces this cultural attitude, which McMahan (2008) connects to the spread of Buddhist mindfulness practices in the West:

"Protestant thinkers, like William Perkins, largely rejected localized, material sacrality—sacred objects, relics, places—which had the effect of leveling the spiritual landscape of the world. In the new Protestant order, no place or object was inherently more sacred than another. This began with the Reformer's assertion that each individual could have unmediated access to God and hence had no need for special places, priests, icons, or rituals." (McMahan 2008, 220)

This cultural backdrop may have facilitated the reception of Cage’s music in America and Europe, especially connecting his aesthetic to audiences without exposure to Zen gardens, Buddhist practice, Muqi’s six persimmons, or the poetry of Méi Yáochén. Cage was, after all, raised Protestant and, in his youth, briefly considered a path in the ministry like his grandfather. Yet this historical context is not essential to understanding his aesthetic. Cage sought a new kind of ordinariness, one that differs in a crucial way from the Western, Protestant affirmation of the everyday. Whereas the latter emphasizes value and significance in ordinary life, the ordinariness Cage cultivated is rooted in emptiness. To realize, as Mǎzǔ Dàoyī does, that "this mind"—commonly translated into English as "ordinary mind"—is the Buddha (即心是仏 jíxīn shìfó), and that even amidst ordinary activities we are already abiding in the sāmadhi of the Dharma-nature, is not simply about valorizing the everyday. Rather, it is about seeing everyday life as it really is: impermanent, fleeting, and apparitional. Affirming the everyday, in this sense, is not about reifying it but about de-reifying it. Recognizing this distinction allows us to appreciate Cage’s music as conveying a mode of attentiveness and equanimity that transcends culturally specific notions of the ordinary.

Muqi's Six persimmons

Musical Means of Ordinariness

Until now, we have identified two primary components in bringing about this mode of listening. By incorporating silences and allowing sounds to possess a medial quality that draws attention to their beginnings, Cage’s music establishes a relationship with ambient sounds that enables the listener to experience everyday life as indeterminate and empty. In a passage already referenced above, Cage elaborates on the musical qualities that produce this mode of listening:

"Just a few weeks ago, I had a very odd experience in a Japanese restaurant in New York. In this restaurant, there was a tape recorder playing Japanese music ... We were conversing as usual while the music was playing. Little by little, during the gaps in our conversation, I realized that the silences included in this music were extremely long, and that the sounds that occurred were very different from each other. I was surprised by my discovery, because the extent of the tape was absolutely unusual, it was very long. And I had never run across that in traditional Japanese music. This piece wasn't destined uniquely for Japanese listeners, but for the entire universe, . . .and it was very, very beautiful. I was unable to recognize any tempo, any periodicity at all. All I was able to identify was the arrival of a few sounds from time to time. I was transported to natural experiences, to my daily life, when I am not listening to music, when sounds simply happen. There is nothing more delicious!" (1981, 119)

In addition to the extremely long silences, the sounds were sparse, contrasting, and without a discernible tempo. The long duration of the piece afforded a patient and leisurely approach to the musical unfolding, allowing the silences to function as much more than mere gaps. Haskins, in a retelling of listening to the Number Pieces that closely mirrors Cage’s restaurant experience, highlights similar qualities:

"Cage's music depends on a slow unfolding and a leisurely approach to time in order to make its full impact. That slow unfolding introduces a graininess or raggedness to the beauty of the sounds. There is no contrast, no epiphany, no drama, no point. The music simply continues with almost annoying steadfastness until its end. That steadfastness, stretched out to extraordinary lengths (seventy minutes or more), allows the music to avoid the trap of merely sounding beautiful." (Haskins u.d.)

This "slow unfolding and leisurely approach to time" gives a functional significance to the silences between notes: they do not become filled with the kind of anticipatory energy or drive typical of Western concert music. Instead, the silences act as spaces in which the listener can encounter the ordinary, everyday life in its openness and indeterminacy. In other writings (“The Distance Between Art and Awakening – Part II,” “Quietness,” and “Pointillism”), I explore additional qualities—non-conceptuality, discontinuity, non-symbolism, blandness, zōka, quietness, and pointillism—that similarly facilitate the enactment of 'ordinary silences' and 'just sounds.'

In this text, the focus is on how the mediality of sounds shapes silence by helping to undo the dualism between ambient and musical sounds. Because the sounds have a particular medial quality, the silences appear as ordinary silences rather than as musical silences. Silences, in turn, are equally important in shaping the medial qualities of sounds. Continuous sound would almost inevitably produce the dualistic veil that Lee and Cage’s aesthetics seek to avoid. Medial sounds, through their aperture, soften the shift to silence and mitigate any sharp edge that could create dualism. Silences also help generate the sense of aperture since the quality of aperture is dependent on something to open up to and from. The qualities of mediality and aperture, then, cannot be located entirely in either sound or silence. Earlier, we suggested that the perception of silences is determined by surrounding sounds, but the reverse is also true: the perception of sounds is shaped by the silences around them.